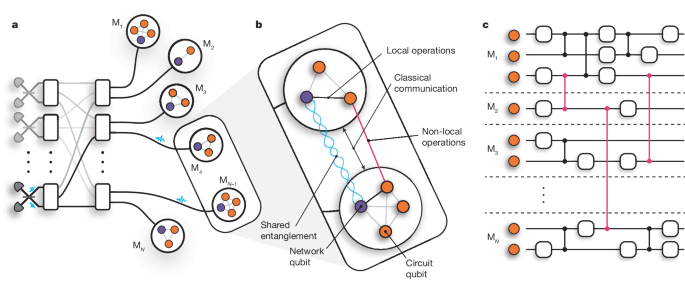

Dual-species ion-trap modules

Our apparatus comprises two trapped-ion processing modules, Alice and Bob. Each module, shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, consists of an ultrahigh-vacuum chamber containing a room-temperature, microfabricated surface Paul trap; the trap used in Alice (Bob) is a HOA-2 (ref. 59) (Phoenix60) trap, fabricated by Sandia National Laboratories. In each module, we co-trap 88Sr+ and 43Ca+ ions. Each species of ion is addressed by means of a set of lasers used for cooling, state preparation and readout. A high-numerical-aperture (0.6 NA) lens enables single-photon collection from the Sr+ ions. A roughly 0.5 mT magnetic field is applied parallel to the surface of the trap to lift the degeneracies of the Zeeman states and provide a quantization axis.

As outlined in the main text, the Sr+ ion provides an optical network qubit, \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{N}}}\), which is manipulated directly using a 674-nm laser. The ground hyperfine manifold of the Ca+ ion provides a circuit qubit, \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\). At about 0.5 mT, the sensitivity of the \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\) qubit transition frequency to magnetic-field fluctuations is 122 kHz mT−1, that is, about two orders of magnitude lower than that of the \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{N}}}\) qubit with a sensitivity of −11.2 MHz mT−1, making it an excellent memory for quantum information37. Furthermore, we define an auxiliary qubit, \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\), in the ground hyperfine manifold of Ca+ for implementing local entangling operations, state preparation and readout. The measured state-preparation and measurement errors for each qubit are presented in Extended Data Table 1.

The spectral isolation between the two species allows us to address one species without causing decoherence of the quantum information encoded in the other species. We make use of this property for sympathetic cooling, mid-circuit measurement and interfacing with the quantum network during circuits.

Quantum process tomography

The action of a quantum process acting on a system of N qubits may be represented by the process matrix χαβ such that

$${\mathcal{E}}(\rho )=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{\alpha ,\beta =0}^{D-1}{\chi }_{\alpha \beta }{P}_{\alpha }\rho {P}_{\beta }^{\dagger },$$

(1)

in which \({P}_{\alpha }\in {{\mathcal{P}}}^{\otimes N}\) are the set of single-qubit Pauli operators \({\mathcal{P}}=\{{\mathbb{I}},{\sigma }_{x},{\sigma }_{y},{\sigma }_{z}\}\) and \(D=\dim ({{\mathcal{P}}}^{\otimes N})={4}^{N}\). Quantum process tomography enables us to reconstruct the matrix χαβ, thereby attaining a complete characterization of the process.

Quantum process tomography is performed by preparing the qubits in the states ρi = |ψi⟩⟨ψi|, in which |ψi⟩ are chosen from a tomographically complete set

$$|{\psi }_{i}\rangle \in \left\{|0\rangle ,\,|1\rangle ,\,\frac{|0\rangle +|1\rangle }{\sqrt{2}},\,\frac{|0\rangle +{\rm{i}}|1\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\right\},$$

(2)

performing the process, \({\mathcal{E}}\), followed by measuring the output state \({\mathcal{E}}[{\rho }_{i}]\) in a basis chosen from a tomographically complete set. Using diluted maximum-likelihood estimation61, the outcomes of the measurements can be used to reconstruct the χ matrix representing the process. In practice, the input states are created by rotating |0⟩ to |ψi⟩ = Ri|0⟩ with

$$\begin{array}{r}{R}_{i}\in \left\{{\mathbb{I}},{\sigma }_{x},\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\mathbb{I}}-{\rm{i}}{\sigma }_{y}),\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\mathbb{I}}+{\rm{i}}{\sigma }_{x})\right\}.\end{array}$$

(3)

Likewise, the tomographic measurements are performed by rotating the output state \({\mathcal{E}}[{\rho }_{i}]\) by \({R}_{j}^{\dagger }\) (equation (3)) and subsequently measuring it in the σz basis. Ideally, this sequence implements the projectors P0,j = |ψj⟩⟨ψj| and \({P}_{1,j}=| {\psi }_{\perp ,j}\rangle \langle {\psi }_{\perp ,j}| \), in which \(\langle {\psi }_{\perp ,j}| {\psi }_{j}\rangle =0\).

However, state-preparation and measurement errors would manifest as errors in the reconstructed process. We therefore model the imperfect state preparation by replacing the ideal input states, |ψi⟩, with the states

$${\rho }_{i}={R}_{i}[(1-{\epsilon })| 0\rangle \langle 0| +{\epsilon }| 1\rangle \langle 1| ]{R}_{i}^{\dagger },$$

(4)

in which ϵ is the state-preparation error. Note that this model assumes that imperfect state preparation leaves the ionic state within the qubit subspace; however, imperfect state preparation often results in leakage outside this subspace. Nevertheless, for the purposes of our analysis, this model is sufficient.

Similarly, we model the imperfect qubit readout by replacing the projectors P0,j and P1,j with the positive-operator-valued measures

$${M}_{0,j}=(1-{{\epsilon }}_{0}){R}_{j}^{\dagger }| 0\rangle \langle 0| {R}_{j}+{{\epsilon }}_{1}{R}_{j}^{\dagger }| 1\rangle \langle 1| {R}_{j}$$

(5)

$${M}_{1,j}=(1-{{\epsilon }}_{1}){R}_{j}^{\dagger }| 1\rangle \langle 1| {R}_{j}+{{\epsilon }}_{0}{R}_{j}^{\dagger }| 0\rangle \langle 0| {R}_{j},$$

(6)

in which ϵ0 and ϵ1 are the computational basis readout errors. The values for these errors are given in Extended Data Table 1.

To quantify the performance of a process, \({\mathcal{E}}\), compared with an ideal unitary process, U, we make use of the average gate fidelity

$${\bar{F}}_{{\mathcal{E}},U}=\int {\rm{d}}\psi \langle \psi | {U}^{\dagger }{\mathcal{E}}(| \psi \rangle \langle \psi | )U| \psi \rangle $$

(7)

as defined by Nielsen62, which corresponds to the fidelity averaged over all pure input states. We define the process \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\prime} }\) as the application of the process \({\mathcal{E}}\) followed by the inverse of the ideal process U, such that

$${{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\prime} }(\rho )={U}^{\dagger }{\mathcal{E}}(\rho )U.$$

(8)

If \({\chi }_{\alpha \beta }^{{\prime} }\) is the process matrix representing \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\prime} }\), as in equation (1), then the average gate fidelity can be expressed as

$${\bar{F}}_{{\mathcal{E}},U}=\frac{1+d{\chi }_{00}^{{\prime} }}{1+d},$$

(9)

in which d is the dimension of the Hilbert space.

Resampling of the measurement outcomes is used to generate new datasets, which are analysed in the same way as the original dataset and are used to determine the sensitivity of the analysis to the statistical fluctuations in the input data. The error bar on the average gate fidelity of a reconstructed process is quoted as the standard deviation of average gate fidelities of processes reconstructed from resampled datasets.

Remote entanglement generation

The heralded generation of remote entanglement between network qubits in separate modules, outlined in ref. 28, is central to our QGT protocol. Spontaneously emitted 422-nm photons entangled with the Sr+ ions are collected from each module using high-numerical-aperture lenses and single-mode optical fibres bring the photons to a central Bell-state analyser, in which a measurement of the photons projects the ions into a maximally entangled state28,63,64. This forms the photonic quantum channel interconnecting the two modules. Following ref. 28, we use a 674-nm π-pulse to map the remote entanglement from the ground-state Zeeman qubit to an optical qubit, which we refer to as the network qubit, to minimize the number of quadrupole pulses in subsequent operations. Successful generation of entanglement is heralded by particular detector click patterns and, after subsequent local rotations, indicate the creation of the maximally entangled Ψ+ Bell state

$$|{\varPsi }^{+}\rangle =\frac{|10\rangle +|01\rangle }{\sqrt{2}}\in {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{N}}}^{\otimes 2}.$$

This process is executed while simultaneously storing quantum information in the circuit qubits, which—as demonstrated in ref. 37—are robust to this network activity.

Each entanglement generation attempt takes 1,168 ns and it takes 7,084 attempts to successfully herald entanglement on average, corresponding to a success probability of 1.41 × 10−4. To mitigate heating of the ion crystal, we interleave 200 μs of entanglement generation attempts with 2.254 ms of sympathetic recooling of the Sr+–Ca+ crystal using the Sr+ ion. The sympathetic recooling comprises 1.254 ms of Doppler cooling, followed by 1 ms of electromagnetically induced transparency cooling. Overall, this results in an average entanglement generation rate of 9.7 s−1 (equivalently, it takes, on average, 103 ms to generate entanglement between network qubits), although this rate could be increased by optimizing the interleaved cooling sequence. This rate is lower than the 182 s−1 rate previously reported in our apparatus28 owing to the extra cooling. We characterize the remote entanglement using quantum state tomography; by performing tomographic measurements on 2 × 105 copies of the remotely entangled state, we reconstruct the density matrix of the network qubits, \({\rho }_{{\rm{N}}}^{{\rm{AB}}}\), shown in Extended Data Fig. 2d. To isolate the fidelity of the ‘quantum link’ in Fig. 2, we account for the imperfect tomographic measurements in the reconstruction of the density matrix using the positive-operator-valued measures in equations (5) and (6). The fidelity of the reconstructed state to the desired Ψ+ Bell state, given by \(\langle {\varPsi }^{+}|{\rho }_{{\rm{N}}}^{{\rm{A}}{\rm{B}}}|{\varPsi }^{+}\rangle \), is 96.89(8)%.

We believe that the fidelity is predominantly limited by errors occurring during the generation of ion–photon entanglement in each module, rather than imperfections in the apparatus used to perform the projective Bell-state measurement. In particular, we attribute the primary sources of error to polarization mixing due to imperfections in the imaging systems used to collect single photons from each module and to drifts in the birefringence of the optical fibres that form the network link between the modules.

Circuit qubit memory during entanglement generation

Because each instance of QGT requires the generation of entanglement between network qubits, it is necessary to ensure that the circuit qubits preserve their encoded quantum information during this process. Owing to their low sensitivity to magnetic-field fluctuations, the circuit qubits have exhibited roughly 100 ms coherence times and, in previous work, we demonstrated these qubits to be robust to network activity37. We further suppress dephasing through dynamical decoupling. Typically, dynamical decoupling is implemented over a fixed period of time; however, the success of the entanglement generation process is non-deterministic and would therefore leave the dynamical decoupling sequence incomplete.

One solution would be to complete the dynamical decoupling pulse sequence once the entanglement has been generated. However, it is desirable to minimize the time between heralding the entanglement generation and performing the QGT protocol, to prevent dephasing of the network qubits. Instead, we make use of the fact that the action of a dynamical decoupling pulse on one of the circuit qubits can be propagated through the teleported CZ gate as

$$({\rm{X}}\otimes {\rm{I}}){U}_{{\rm{CZ}}}={U}_{{\rm{CZ}}}({\rm{X}}\otimes {\rm{Z}}).$$

(10)

We therefore perform the dynamical decoupling pulses on the circuit qubits until we obtain a herald of remote entanglement, at which point we immediately perform the QGT sequence—implementing a CZ gate on the state of the circuit qubits at the point of interruption. Once this gate is completed, we perform the remaining dynamical decoupling pulses (without any interpulse delay) and use equation (10) to apply the appropriate Z rotations required to correct for the propagation through the CZ gate. With this method, we suppress the dephasing errors in the circuit qubits during entanglement generation while minimizing the time between successfully heralding the entanglement and consuming it for QGT.

We deploy Knill dynamical decoupling65,66 with a 7.4-ms interpulse delay (corresponding to a pulse every three rounds of interleaved entanglement attempts and recooling). We use quantum process tomography to reconstruct the process of storing the quantum information while generating entanglement; ideally, this process would not alter the quantum information stored in the circuit qubit. Quantum process tomography is implemented by choosing input states for the circuit qubits from the tomographically complete set given in equation (2), generating remote entanglement between the network qubits while dynamically decoupling the circuit qubits, then—on successful herald—completing the dynamical decoupling sequence and performing tomographic measurements of the circuit qubits. The reconstructed process matrices for each module corresponding to the action of storing quantum information during entanglement generation are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2c. We observe fidelities to the ideal operation of 98.1(4)% and 98.2(5)% for Alice and Bob, respectively.

Local mixed-species entangling gates

The ability to perform logical entangling gates between ions of different species allows us to separate the roles of network and circuit ions. We implement mixed-species entangling gates following the approach taken in ref. 40, in which geometric phase gates are deterministically executed using a single pair of 402-nm Raman beams, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 3. Here we apply the gate mechanism directly to the network qubit in Sr+—rather than the Zeeman ground-state qubit, as done by Hughes et al.40 and Drmota et al.37—at the cost of a slightly reduced gate efficiency that is compensated for by the use of higher laser powers. This enables us to perform mixed-species CZ gates between the network and auxiliary qubits. We characterize our mixed-species entangling gates using quantum process tomography in each module, reconstructing the process matrices χCZ representing the action of the local CZ gate acting between the network and auxiliary qubits. The reconstructed process matrices for each module are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3d. Compared with the ideal CZ gate, we observe average gate fidelities of 97.6(2)% and 98.0(2)% for Alice and Bob, respectively.

Hyperfine qubit transfer

Because the circuit qubit does not participate in the mixed-species gate, the gate interaction is performed on the network and auxiliary qubits. Consequently, we require the ability to map coherently between the circuit and auxiliary qubit before and after the local operations. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 4, this mapping is performed using a pair of 402-nm Raman beams detuned by about 3.2 GHz, to coherently drive the transitions within the ground hyperfine manifold of Ca+.

The transfer of the circuit qubit to the auxiliary qubit begins with the mapping of the state |0C⟩ to the state |0X⟩. However, owing to the near degeneracy of the transition \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{0}:|{0}_{{\rm{C}}}\rangle \leftrightarrow |F=3,{m}_{F}=+1\rangle \) and the transition \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{1}:|{1}_{{\rm{C}}}\rangle \leftrightarrow |F=4,{m}_{F}=+1\rangle \) (Extended Data Fig. 4), separated by only about 15 kHz, it is not possible to map the |0C⟩ state out of the circuit qubit without off-resonantly driving population out of the |1C⟩ state. We suppress this off-resonant excitation using a composite pulse sequence, shown in (1) in Extended Data Fig. 4b, comprising three pulses resonant with the \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{0}\) transition, with pulse durations equal to the 2π time of the \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{1}\) transition, and phases optimized to minimize the off-resonant excitation. This pulse sequence allows us to simultaneously perform a π-pulse on the \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{0}\) transition and the identity on the off-resonantly driven \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{1}\) transition. Raman π-pulses are then used to complete the mapping to the |0X⟩ state. Another sequence of Raman π-pulses coherently maps |1C⟩ → |1X⟩, thereby completing the transfer of the circuit qubit to the auxiliary qubit, \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\to {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\). To implement the mapping \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\to {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\), the same pulse sequence is applied in reverse.

We characterize our \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\leftrightarrow {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) mapping sequence by performing a modification of single-qubit randomized benchmarking (RBM), in which we alternate Clifford operations on the \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) qubits, as illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 4c. We assume that (1) the single-qubit gate errors for the \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) qubits are negligible compared with the \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\leftrightarrow {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) transfer infidelity (we typically observe single-qubit gate errors of around 1 × 10−4 for the Ca+ hyperfine qubits) and (2) the fidelity of the transfer \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\to {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) is similar to \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\to {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{C}}}\). We therefore we model the survival probability as

$$S(m)=\frac{1}{2}+B{p}^{m}$$

in which m is the number of hyperfine transfers, B accounts for state-preparation and measurement error offsets and p is the depolarizing probability for the transfer, related to the error per transfer as

$${{\epsilon }}_{{\rm{C}}\leftrightarrow {\rm{X}}}=\frac{1-p}{2}.$$

The RBM results are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4c; we measure an error per transfer of 3.8(2) × 10−3 (2.6(1) × 10−3) for Alice (Bob).

Conditional operations

To complete the QGT protocol, the two modules perform mid-circuit measurements of the network qubits, exchange the measurement outcomes and apply a local rotation of their circuit qubits conditioned on the outcomes of the measurements. By virtue of the spectral isolation between the two species of ions, mid-circuit measurements of the network qubits can be made without affecting the quantum state of the circuit qubits. The mid-circuit measurement outcomes, mA, mB ∈ {0, 1}, are exchanged in real time through a classical communication channel between the modules—in our demonstration, this is a TTL link connecting the control systems of the two modules. Following the exchange of the measurement outcomes, the modules, Alice and Bob, perform the conditional rotations UA and UB, respectively, in which

$$\begin{array}{l}{U}_{{\rm{A}}}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{S}^{\dagger } & \text{if}\,{m}_{{\rm{A}}}\oplus {m}_{{\rm{B}}}=0,\\ S & \text{otherwise}\,,\end{array}\right.\\ {U}_{{\rm{B}}}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}S & \text{if}\,{m}_{{\rm{A}}}\oplus {m}_{{\rm{B}}}=0,\\ {S}^{\dagger } & \text{otherwise}\,,\end{array}\right.\end{array}$$

in which S = diag(1, i).

Errors in the mid-circuit measurements of the network qubits will result in the application of the wrong conditional rotation; effectively, this would appear as a joint phase flip of the circuit qubits following the teleported gate. The mid-circuit measurement errors arise from the non-ideal single-qubit rotation of the network qubit to map the measurement basis onto the computational basis and errors owing to the fluorescence detection of the network qubit. Using RBM, we measure single-qubit gate errors for the network qubits of 4.8(3) × 10−4 and 9.8(3) × 10−4 for Alice and Bob, respectively. The error in the fluorescence detection is estimated from the observed photon scattering rates of \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{N}}}\) states, as well as the approximately 390 ms lifetime of the |1N⟩ state67. We choose a mid-circuit measurement duration of 500 μs and estimate fluorescence detection errors of 6.6(1) × 10−4 and 5.51(2) × 10−4 for Alice and Bob, respectively. Combining these error mechanisms, we estimate contributions to the teleported CZ gate error of 0.091(3)% and 0.122(2)% for Alice and Bob, respectively.