Researchers who get their start in small groups are more likely to stick with academia than those trained in large groups, analysis shows. Credit: Daniel Munoz/AFP/Getty

Postdoctoral students, graduate students and other junior scientists in large research groups are more likely to drop out of academia than are their peers in smaller groups, according to a new study of more than one million early-career researchers.

But the analysis also found that researchers trained in large groups who stay in academia have more career success. The work was published Monday in Nature Human Behaviour, amid a mass exodus of scientists from academia and a mental-health crisis among PhD students.

The findings are consistent with past anecdotal studies and survey results, but this is the first attempt to quantify the effects of different types of scientific mentorship, says co-author Roberta Sinatra, a social-data scientist at the University of Copenhagen.

“I hope that this helps guide the choices of PhD students,” she says.

Burnout and dropout

Sinatra and her team analysed academic mentorship networks using two data sets: the crowd-sourced website Academic Family Tree, which includes global records of scientists, their advisers and their students in more than 50 academic fields, and the online research catalog OpenAlex, which features records of authors and their papers, institutions and citations. Their final data set included about 1.5 million scientists and 1.8 million mentorships in chemistry, physics and neuroscience. These fields had enough long-term data for the authors’ analysis and are heavily represented in the family-tree website.

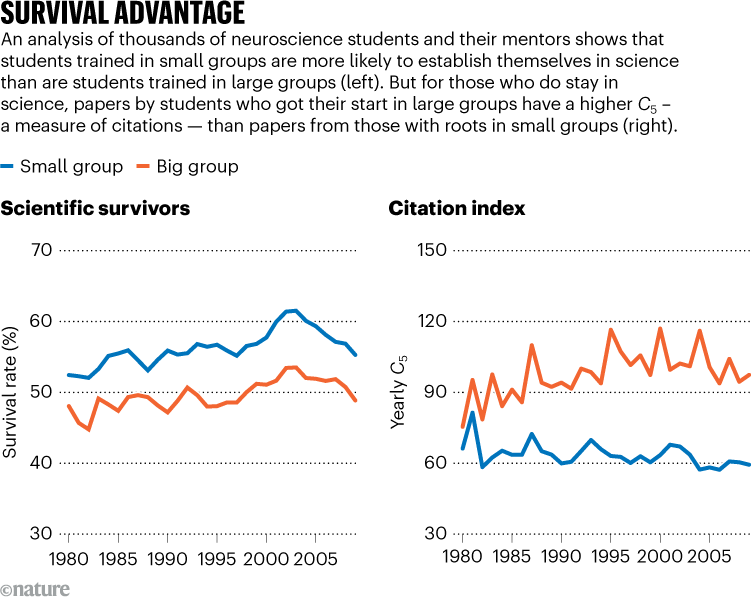

The results showed that the percentage of researchers who remain in science for at least ten years is lower for those who were trained in big groups than for those who were trained in small groups (see ‘Survival advantage’). Between the 1980s and 1995, for example, the “survival rate” of big-group protégés was 38–48% lower than that of their small-group counterparts.

However, the big-group scientists publish papers that score higher on an index measuring average citations per year, and are more likely to be ranked among the most-cited scientists.

Source: Ref. 1

To understand why some big-group protégés succeed, the study’s authors examined papers on which a protégé was the first author and their mentor was the last author ― which suggests that the trainee had received substantial attention from their mentor. Big-group scientists who survived in academia had published “notably” more of these first-author papers than had the dropouts, the paper says.

“Now we also have quantitative evidence that attention is important,” says Sinatra. “It’s not simply speculation.”