- Sri Lanka’s isolation during past glacial cycles resulted in the evolution of unique species, but ongoing human-induced climate change now poses a major threat to their survival.

- Using species distribution models, researchers have discovered that montane amphibians and reptiles that are particularly restricted to narrow ecological niches with limited mobility are particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures.

- Species with direct development, like many Pseudophilautus frogs, which bypass the tadpole stage, are especially sensitive to microclimate changes.

- Of the 34 amphibian species confirmed extinct worldwide, 21 were endemic to Sri Lanka, underscoring the island’s fragility and the urgent need for targeted conservation efforts.

COLOMBO – During the Ice Ages, there was a decrease in global sea levels, creating a land bridge between Sri Lanka and India, only to have the then-warmer interglacial periods reverse this, isolating the Indian Ocean island.

This triggered cycles of connection and separation that enabled gene flow with the mainland, followed by periods of isolation that drove speciation resulting in the rich biodiversity Sri Lanka harbors today.

A recent study is offering fresh insights into how human-induced climate change may be reversing this evolutionary success story. The very species that evolved as endemics during these ancient climatic shifts are today among the most at risk.

“We analyzed 233 endemic vertebrate species, including amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals” says Iresha Wijerathne of Guangxi University, lead author of the study. While Sri Lanka is home to 370 endemic vertebrates, including 101 amphibians, 154 reptiles, 34 birds and 20 mammals, only 233 had sufficient data for modeling. The researchers used species distribution modeling (SDM) techniques to project the impacts of climate change by 2100.

SDM uses environmental variables like temperature, rainfall, elevation and vegetation to predict how suitable habitats for a species may shift over time. These projections are critical for habitat-specific species with limited ranges, particularly endemics.

Globally, climate change is expected to alter species distributions through rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns and more frequent extreme weather events. Even modest increases — an average of 1.5 ° Celsius (2.7 ° Fahrenheit) by 2040, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — can displace suitable habitats, leading to population declines or extinction. Endemic species, with narrow ranges and limited dispersal, are especially vulnerable, Wijerathne says.

Amphibians and reptiles at highest risk

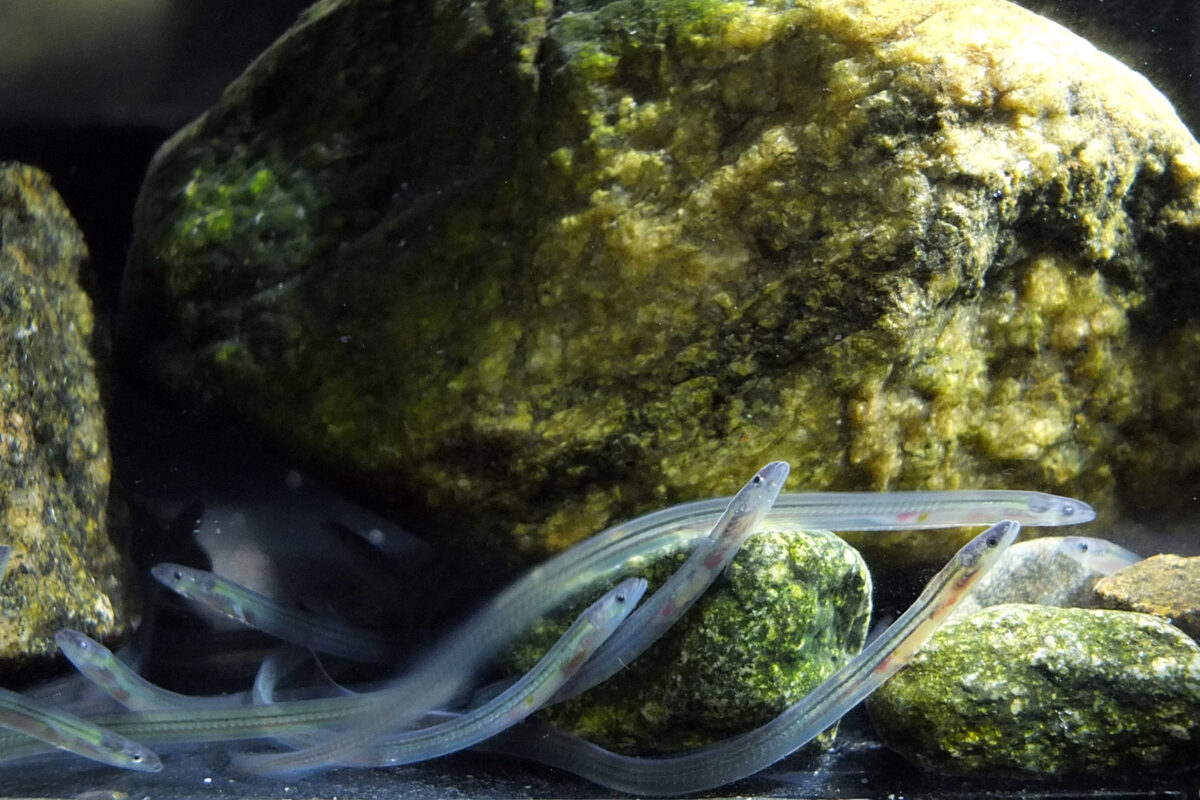

“Amphibians and reptiles emerged as the most vulnerable groups,” says study co-author Madhava Meegaskumbura, a professor in evolutionary genetics at Guangxi University. Among them, species with direct development, which is a reproductive strategy where amphibians hatch as miniature adults without a tadpole stage, are particularly at risk.

“These frogs evolved to thrive in stable, moist environments, laying eggs in terrestrial habitats,” says Meegaskumbura, who has studied Sri Lanka’s amphibians for decades. “But this very adaptation now limits them to shrinking climatic niches, especially in high-elevation cloud forests.”

Sri Lanka has already recorded the highest number of amphibian extinctions globally. Of the 34 confirmed amphibian extinctions worldwide, 21 were from Sri Lanka, 17 of them from the genus Pseudophilautus, a group of direct-developing frogs. Many critically endangered Sri Lankan frogs share these traits and are highly dependent on high humidity for their eggs to develop.

“With climate warming, suitable habitats on mountaintops are diminishing. These frogs have nowhere higher to go,” Meegaskumbura tells Mongabay. He adds that species like cloud forest-dwelling horned lizards (Ceratophora spp.) that have been restricted to cool, moist environments may face similar threats. Meegaskumbura calls for more research to understand their physiological limits.

Unknown climate risks

The study, however, did not include freshwater fish or invertebrates of Sri Lanka. Limited research exists on Sri Lanka’s invertebrates beyond butterflies, bees, dragonflies, spiders and crabs. However, many of these species, particularly those with poor dispersal ability or limited climatic ranges, are likely to face similar risks due to climate change, Meegaskumbura noted.

The research team highlights the urgent need for more data, especially on the functional genomics of narrowly distributed species. Understanding how organisms might respond to rapid environmental shifts is key to shaping adaptive conservation strategies.

Although mammals and birds may be less immediately impacted due to their mobility and broader ecological tolerance, they may also not be completely immune to the changing climate. A global review estimates that biodiversity hotspots could lose up to 31% of their biodiversity by 2100, with island ecosystems being especially vulnerable.

Conservation urgency

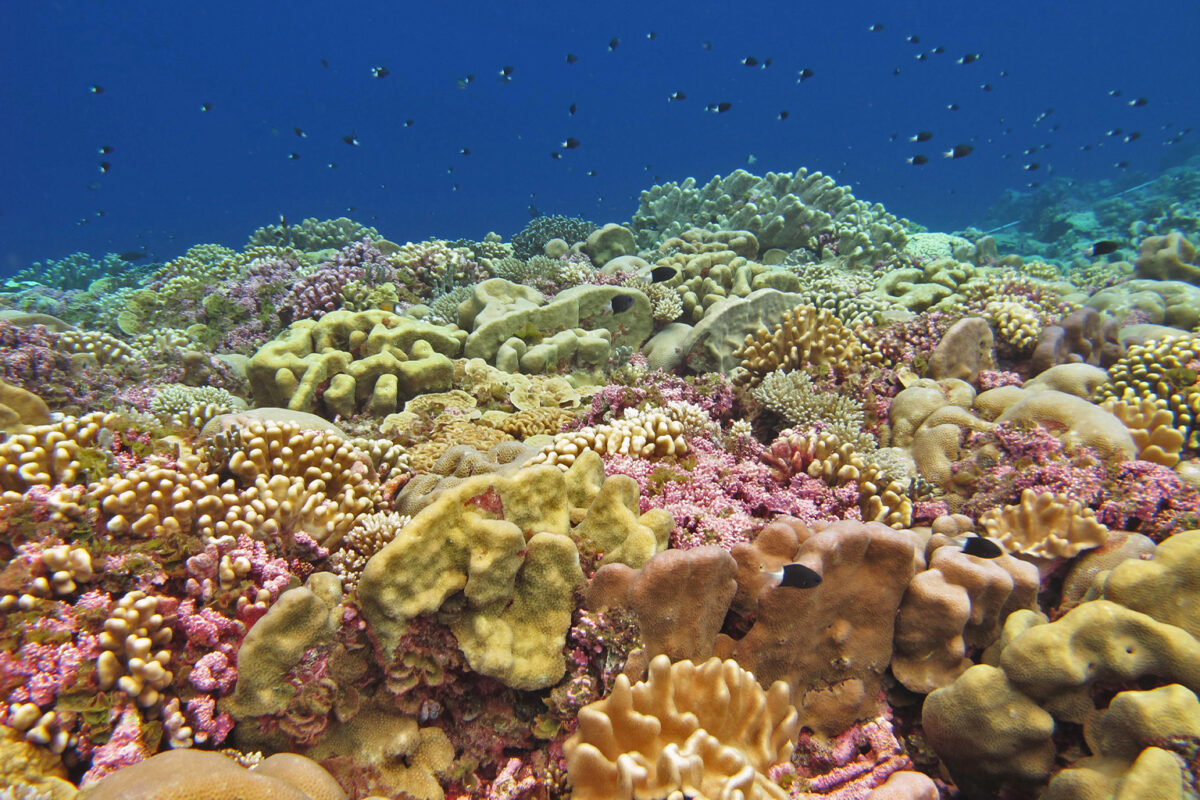

Sri Lanka, as part of the Western Ghats–Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot, faces not just climate change but also intense human pressures: deforestation, habitat fragmentation and land use change. These combined threats heighten the urgency for informed, climate-resilient conservation efforts.

Silent encroachments for agriculture, such as tea and cardamom plantations, especially in biodiversity hotspots like eastern Sinharaja are fragmenting habitats critical for many endemic species. “We need to preserve the forest’s full structure from leaf litter to canopy to protect unique horned lizards like C. karu and C. erdeleni that live in different forest layers,” said co-author and herpetologist Suranjan Karunarathna of the Nature Explorations & Education Team.

Some parts of the biodiversity-rich eastern Sinharaja are no longer the same as they were two decades ago, Karunarathna says. In a recent survey, researchers were unable to find certain species in areas where they had been previously recorded, according to Karunarathna.

“We need strategies that integrate future climate projections with current land use patterns,” Wijerathne adds. “Proactive measures, such as habitat restoration and protection in mountainous and catchment areas, are critical if we are to preserve Sri Lanka’s unique biological heritage.”

Banner image: Poppy’s shrub frog (Pseudophilautus poppiae), a critically endangered species living in Sri Lanka’s cloud forest area, is especially vulnerable to climate change. Image courtesy of Sanoj Wijayasekara.

Citations:

Wijerathne, I., Deng, Y., Goodale, E., Jiang, A., Karunarathna, S., Mammides, C., Meegaskumbura, M., Vidanapathirana, D.R., Zhang, Zhixin. (2025). The vulnerability of endemic vertebrates in Sri Lanka to climate change. Global Ecology and Conservation, 59, e03515.

Bossuyt, F., Meegaskumbura, M., Beenaerts, N., Gower, D. J., Pethayagoda, R., Roelants, K., … Milinkovitch, M. C. (2004). Local Endemism Within the Western Ghats-Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot. Science. Retrieved from

Bellard, C., Leclerc, C., Leroy, B., Bakkenes, M., Veloz, S., Thuiller, W., & Courchamp, F. (2014). Vulnerability of biodiversity hotspots to global change. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 23(12), 1376-1386. doi:10.1111/geb.12228