- Conservationist Farina Othman, a 2025 Whitley Award winner, has been working with endangered Bornean elephants in Sabah, Malaysia, since 2006.

- Since the 1970s, logging, oil palm plantations and roads have reduced and fragmented elephant habitats, increasing contact between the animals and humans; retaliatory killings arising from human-elephant conflict are now among the major threats to the species’ survival.

- Equipped with knowledge of the Bornean elephant’s behavior, Othman works with local communities and oil palm plantations to promote coexistence with the elephants.

- In a recent interview with Mongabay, Othman dives deep into the human-elephant conflicts in the Lower Kinabatangan area, explaining why and how she attempts to change communities’ perceptions of elephants and reconnect elephant habitats.

In 2006, Farina Othman heard a loud boom when she was observing a group of Bornean elephants in a forest in the Lower Kinabatangan area, one of the largest floodplains in Malaysia. She recognized that it was the sound from a bamboo cannon. It’s a type of homemade firecracker locals use to chase elephants away.

At that time, she had just started her master’s studies, focusing on Bornean elephants (Elephas maximus borneensis). She felt humans were being unfair to the elephants. Determined to help, she decided to step in to be their voice.

Today, only about 1,000 Bornean elephants remain in the wild, mainly in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. In 2024, the species was listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The plight of the Bornean elephants began in the 1970s. Between 1973 and 2010, Sabah lost more than 52% of its lowland forest (below 500 meters, or 1,640 feet, above sea level) to logging. Many of these lands were later converted into oil palm plantations. For the Bornean elephants, more than half of their ideal habitat is gone.

Othman, now in her early 40s, has become a Bornean elephant conservationist and teaches at Universiti Malaysia Sabah. She told Mongabay that habitat loss and fragmentation fuel human-elephant conflict. “They don’t want to live or share the landscape with the elephants,” Othman said of some local communities.

Despite being protected by law, the elephants face retaliatory killings by gun or poison.

In 2018, Othman founded Seratu Aatai, an organization promoting coexistence between local communities, palm oil companies and the Bornean elephants. In recognition of her work, she received the 2025 Whitley Award in April. Next, she aims to unite plantations in a coordinated effort to protect the species — an approach that is not always common in conservation.

In a recent interview with Mongabay, Othman discussed the current conflict situation, working with oil palm plantations and the government to reconnect elephants’ habitats and how she plans to shift public perceptions of the elephants.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mongabay: What inspired you to work on Bornean elephant conservation?

Farina Othman: My journey in conservation started in 2003 when I did my first degree in conservation biology at Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

For my final-year project, I wanted to prove whether it was true that people say our Bornean elephants were pygmy elephants. So, I measured them in a small zoo in Kota Kinabalu. I found that there is no significant difference in body size between the elephants in Peninsular Malaysia and those in Sabah, despite the common assumption that Bornean elephants are smaller.

That was when I got to know their personality.

Mongabay: How would you describe their personality?

Farina Othman: Through field observations, I learned that each Bornean elephant has a unique personality. Some were more curious, while others were shy or more dominant. What stood out the most was their tendency to avoid people whenever possible, maybe shaped by their experiences with human activity.

One of the biggest lessons I learned was the importance of respecting their cues. Even if you’re just a few feet away, you have to be fully aware of their signals. The way they move, how they position their ears or trunks. They’re constantly communicating, and if you don’t pay attention, you risk crossing a line.

That early experience taught me to listen with more than just my ears, to respect their space, their comfort and their boundaries.

Mongabay: When was your first encounter with a wild Bornean elephant? How was the experience?

Farina Othman: In 2006, I did my master’s degree under Benoît Goossens. At that time, he was doing his post-doctoral studies on the conservation genetics of Bornean elephants.

That was my first time seeing wild Bornean elephants. It was a group of about 20 female elephants feeding in the forest. Suddenly, we heard a loud noise.

That was a deep boom, like a controlled explosion echoing through the forest. Back then, it was common for people to use bamboo cannons to create loud noises like that.

You know, that was in the forest, not outside the forest. People wanted to keep the elephants from entering the plantation.

But these elephants are in their own home, in the forest. They’re not doing anything. They’re just feeding and moving around. But we are harassing them, provoking them.

I thought that we misunderstood many of their behaviors. I felt it was my responsibility to become their voice. That’s how everything started.

Mongabay: You said you heard loud noises from people, but you were in a forest, right? Where do they come from?

Farina Othman: You know, the forests in Kinabatangan are surrounded by oil palm plantations.

Elephants like lowland, flat land. They can use some hilly areas, but they will try to avoid them. But flat lands are also suitable for planting oil palms. So, much of their habitat has already been converted to oil palm plantations.

In Kinabatangan, the wildlife sanctuaries are very small. Now, the oil palm plantations are doing a lot of replanting. So there are chipping areas, where the elephants are attracted to their shredded palms. A lot of food. Very sugary. It’s like a food festival for them. Elephants are [also] attracted to the young oil palms, which they find palatable.

But more importantly, in many areas, elephants have no choice. The plantations have cut through or replaced their traditional routes to move around, so they’re forced to use oil palm estates.

When [the elephants] move from one forest block to another block, you have oil palm plantations or villages in between. So, elephants are forced to move through people’s land. That means more contact with people. This is where all the conflicts happen.

Mongabay: What exactly is happening on the ground, in villages and plantations?

Farina Othman: Imagine if elephants come and walk in front of your house or near your car. They are big; you will feel scared. You’ll always think that they will come and attack you.

Many people feel insecure in the presence of elephants, although the elephants are not doing anything. If elephants start eating their crops, it will upset them even more. So, it is the feeling of insecurity, crop losses and property damages.

They also feel that they are alone. When they report the situation to the authority, they might get late responses, or the elephants keep coming back after being pushed away. So, they feel frustrated and their tolerance level goes down. They don’t want to live or share the landscape with the elephants. That’s the situation now.

In many cases, people lodge complaints and push for measures like fencing up their plantations to keep elephants out. While this reaction is understandable from a livelihood protection standpoint, it often leads to further fragmentation of elephant habitats. It restricts their natural movement, which can increase stress on the animals and even escalate human-elephant conflict in the long run.

Many people want a simple and fast solution. But the solution to conflicts is usually very complex.

We also have human-human conflict. For example, I’m a conservationist; I have my idea on how we can manage elephants. But villagers or plantation managers may not think solving their conflict with elephants is their responsibility. So, we have different opinions and views about the elephants.

This is the hardest part to solve in the human-elephant conflict.

Mongabay: Has it ever come to fighting or violence? Or just verbal disagreements?

Farina Othman: So far, it’s been limited to verbal disagreements.

Mongabay: So, how do you overcome this human-human conflict?

Farina Othman: It takes a lot of follow-ups and transparency. You have to stay focused on your intention. There must be a very focused leader. That’s why Seratu Aatai doesn’t work on multiple species. We need long-term commitment if we want to make changes.

And you have to build trust. You must share resources.

That’s why we call ourselves Seratu Aatai, which means bersatu hati [“united in spirit” in Malay]. Everyone needs to come together.

Mongabay: But how do you convince the plantation companies to join you?

Farina Othman: First of all, if a plantation wants to get certified as sustainable palm oil, it needs to show that it has put effort into reducing conflict or considering the welfare of endangered species in the plantation. Some planters also told us they must give back to nature because they know their business depends on it. For example, their yield depends on the soil’s health.

But planters also have their own goals. Their performance is not being assessed by how many elephants they saved or how many trees they planted. It’s about how much fruit they produced.

If you check the RSPO [Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil] and MSPO [Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil] criteria, biodiversity conservation is just one tiny part.

They are planters by training; now you expect them to do conservation. Of course, they feel overwhelmed. In the survey that we did with them, they said, ‘Whatever we try to do, people will still blame us.’ They feel discouraged.

So, we need to be with them and work with them. We need to understand the barriers and see how we can find a win-win situation for wildlife and them.

Mongabay: How long did it take you to gain their trust and get to this stage?

Farina Othman: It takes a long time.

For example, I’ve been working with one plantation since 2017. Now, we are going to get their neighbors, the plantations surrounding this one plantation, to join forces.

Mongabay: How many companies do you target to work with?

Farina Othman: Under the Whitley Award, we aim to get seven plantations together to form a consortium. They are around the Sukau area.

Mongabay: What do the oil palm plantations have to do if they join the consortium?

Farina Othman: For now, the idea is to try to share resources. We want to implement the conservation program together. We don’t want to tell them what they must do when we don’t understand what their challenges are.

We want to decide together what we need to do to reduce conflicts, so the elephants can still use the area. For example, if we need to create a corridor, we must decide together where to make it. Then, we’ll try to enrich it with elephant food plants so that elephants will use it.

Mongabay: You’ve mentioned sharing resources a few times now. What are the resources that need sharing?

Farina Othman: It’s technical input and funding.

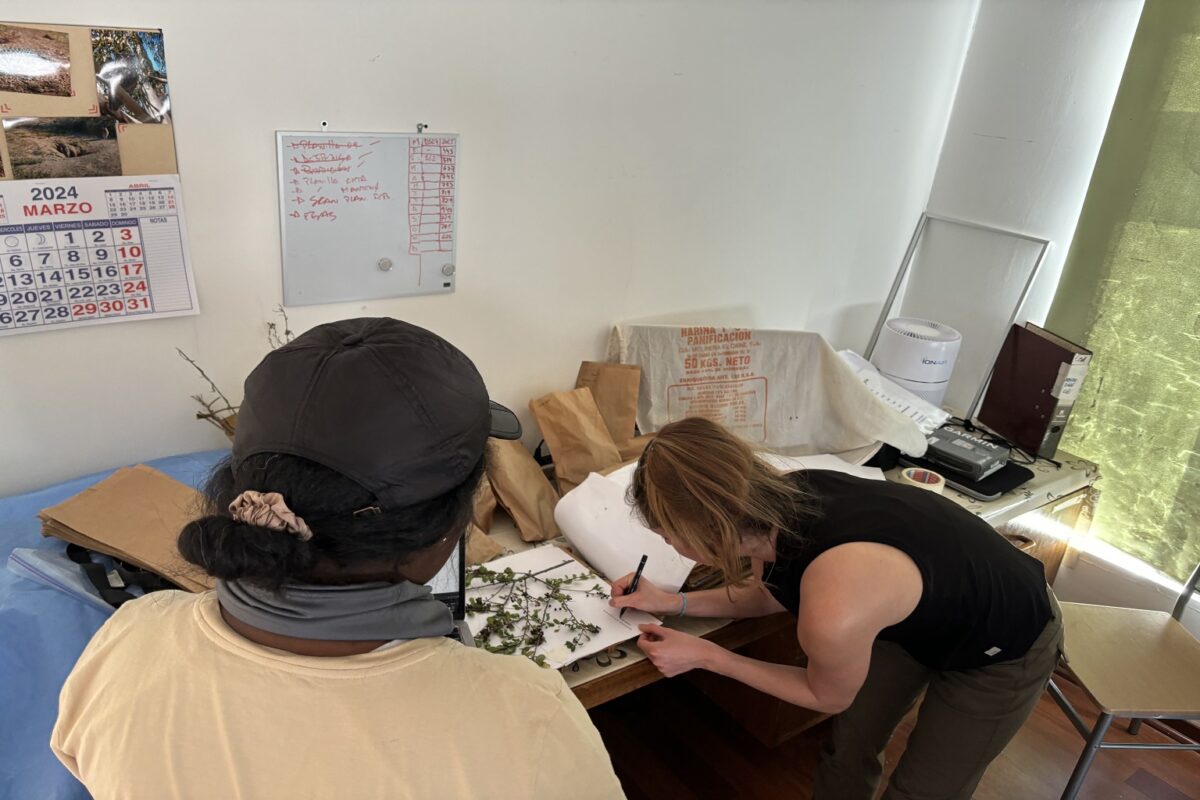

You need to plan a conservation program based on data — scientific data, not your feelings or emotions. So, we need to understand what the elephants tell us. That’s what Seratu Aatai can contribute. Because we understand elephant movement and behavior.

The plantations will tell us how much time, workforce and money they can spend on conservation. Then, we can try to get to the middle ground.

Most of our field staff come from the local communities. While they may not initially have formal scientific training, we provide them with hands-on training and expose them to researchers and scientists who collaborate with us. Some of them do hold university degrees, and we actively support and encourage their further education.

Our approach is to build local capacity because the people who live closest to the elephants are often the most committed to protecting them when given the opportunity and support.

Mongabay: Just now, you gave an example of having plantation companies set up a wildlife corridor together. What’s the problem with elephants passing through the plantations without the corridor?

Farina Othman: The problem is that everyone doesn’t know where to divert the elephants.

For example, if elephants come into your area, you might push them to my area. Then I’ll do the same. So, we are pushing the elephants into each other’s land, which makes the elephants more confused and they will stay there longer. That means a higher possibility for injuries, crops and property damage.

But once we have a passage for elephants, both you and I will try to divert the elephants toward it. We know the passage will connect them to the wildlife sanctuaries.

It’s not only about giving space for the elephants; it’s also about the unity among all the plantations. When you’re dealing with the conflict as a team, you feel supported. Hopefully, that will increase your tolerance toward the elephants.

And, you share resources. Right now, everyone is putting electric fences on their plantations. But it is a cost to maintain it. That’s why plantations don’t want to have elephants. But if you are to maintain only one integrated electric fence, you save resources.

Mongabay: We’ve talked about solving human-human conflict to reduce human-elephant conflict. What about the direct human-elephant conflict? How do you solve it?

Farina Othman: There is no one, single solution to this issue. Again, the human-human conflict is the most difficult part. And we need political will.

For example, everyone on the ground tries to make a wildlife corridor. Suddenly, one government wants to build a bridge that will further destroy the elephant habitats. Then, everything that we’ve been working on will be gone.

Changing the way we do things is very slow. It’s not something that you can do in one year, two years or 10 years. It takes generations.

But slowly, I want to change the way we see the issue now. For example, instead of using the word halau [“chase away” in Malay], we say iring gajah tu keluar [“walk the elephant out” in Malay]. This is what I can do within my control.

Another example is that we don’t call our workshop a human-elephant conflict workshop. We change it to bengkel pengurusan lawatan gajah [“elephant visits management workshop” in Malay].

Mongabay: [Laughed] Lawatan gajah? ‘Elephant visits?’

Farina Othman: Yes, exactly. We want to change the negative perception. I know it’s hilarious, but people will come with a positive vibe. Because they feel, ‘I have the power, because I am managing. I’m not the victim.’

If not, people come with the perception, ‘I’m the victim,’ they’ll never feel it’s their responsibility to resolve the conflict.

Mongabay: Do you also study psychology or social science?

Farina Othman: No. But I try to work more with social scientists now. I’m very lucky that my husband is a social scientist. He has been helping me to understand that a lot.

Mongabay: What are some memorable experiences you have had at work?

Farina Othman: It is wonderful to see elephants living freely, like feeding and just moving around in their habitat.

Sometimes, it’s when we reunite a lost baby elephant with its family or introduce it to a new family herd. We’ve done that a few times.

The hard moment is when we have to do translocation. That is quite sad for me because translocating an elephant will not solve the issue. It will just transfer the issue to another area. It’s also dangerous for the elephant, psychologically and physically.

Usually, elephants are translocated because they spend too much time in a particular area, often near human settlements or plantations, and people start seeing them as a threat. Sometimes, the elephant is labeled as ‘rogue,’ especially if there’s damage to crops or property.

But behind those decisions lie complex human-elephant tensions, fear, frustration and sometimes, a lack of alternative options. It’s emotionally challenging because you know the elephant isn’t trying to be a problem. It’s just trying to survive in a landscape that has changed so much.

The most frustrating thing is when developments happen and you don’t get involved from the beginning.

Like the government wanted to build a highway [the Pan Borneo Highway], we gave them recommendations to avoid the sensitive area, but they said it’s expensive. But in the long run, it will be even more expensive, because the conflict can cause accidents. It can cost both human and elephant lives. But we still choose not to invest.

We’re not against development, we understand its importance. But you have to think long-term. I’m talking about Tawai [Forest Reserve]. For many years, we tried to convince the government using data, and we did many surveys.

There were years when they said they’ll cancel it. But now, they’re going to build it.

Mongabay: Back then, you and other organizations suggested alternative alignments to the Pan Borneo Highway to avoid cutting through the Tawai, which is a Bornean elephant habitat in central Sabah. Did the road alignment shift eventually?

Farina Othman: No.

But we had a good discussion with JKR [the Public Works Department]. They’re willing to try to include some sort of passage for elephants and other wildlife now. Not a viaduct, because they said it is too expensive. They want to design something using less expensive materials.

Mongabay: Will Seratu Aatai continue doing anything about the highway in Tawai?

Farina Othman: Yes, we are working with the Coalition 3H [a united group working on planning and infrastructure] again. We got funding from Yayasan Hasanah to study wildlife and elephant movement in that area. Now, we are putting camera traps along the alignment where they want to build the road.

Hopefully, we can still advise the government on where to put wildlife crossings and study the impact before and after the highway.

I think that’s the best we can do to reduce the impact in Tawai. Hopefully, we will learn some lessons for a longer stretch of the highway in Kalabakan. That is the more sensitive area for Bornean elephants.

Mongabay: What is the one message you would share with other conservationists who are also trying to solve human-wildlife conflict in their area?

Farina Othman: I don’t have the answer right now, because the situation in each area would be different.

But I think for us, it’s about transparency. It’s about keeping the right intention. We’re not there because of money or to showcase our organization. This is not about the organization; this is about the animals. So, you’ll do anything to make sure it benefits the species. Then you’ll feel it doesn’t matter who gets the credit.

Mongabay: Is there anything else you think Mongabay readers should know?

Farina Othman: As Malaysians, we must take this responsibility. I know it’s complex. We, the young generation, must push ourselves out of our comfort zones.

If we don’t take this responsibility, I don’t think anyone else will do it, and we’ll spend a lot of money to revive what has been destroyed.

There must be reasons why our old folks created proverbs like menyesal dulu pendapatan, menyesal kemudian tak ada guna [“Regretting beforehand is foresight; regretting afterwards is useless” in Malay] and sediakan payung sebelum hujan [“Prepare the umbrella before it rains” in Malay].

If you’re passionate about something, you just have to go for it and find the opportunities to do it. I want to motivate Malaysians that it is time for us to step up.

Banner image: A herd of female and young Borneo elephants eat chipped palms in a plantation. Image © Oregon Zoo/Shervin Hess.

You can move an elephant to the jungle, but it won’t stay there, study says

Citations:

Abram, N. K., Skara, B., Othman, N., Ancrenaz, M., Mengersen, K., & Goossens, B. (2022). Understanding the spatial distribution and hot spots of collared Bornean elephants in a multi-use landscape. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1-16. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-16630-4

Estes, J. G., Othman, N., Ismail, S., Ancrenaz, M., Goossens, B., Ambu, L. N., Estes, A. B., & Palmiotto, P. A. (2012). Quantity and configuration of available elephant habitat and related conservation concerns in the Lower Kinabatangan floodplain of Sabah, Malaysia. PLOS One, 7(10), e44601. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044601